Conquistadors truly do mess up whatever–.

The idol was revered at Pachacamac for 700 years before Spanish conquest.

Kiona N. Smith

–

.

Sepulveda et al. 2020

.

The idol of Pachacamac was currently 700 years old when Spanish conquistadors gotten here in Peru, according to radiocarbon dating of the wood.

Long-lost colors

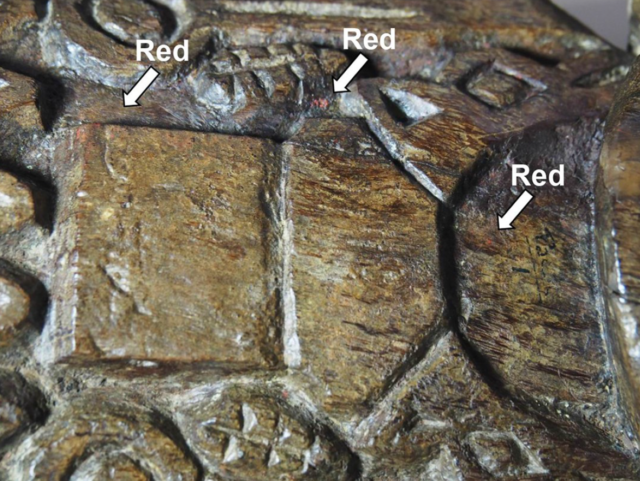

After roughly 1,300 years, the carvings on the surface of the oracle still make it through in abundant information. As elaborate as the carvings are, they’re missing something important: color.

Much of the color of the ancient world has actually been lost to us for centuries, and modern-day innovations are just starting to show us how vivid the previous actually was. Greek and Roman statues weren’t sterile white; medieval cathedrals had plenty of color; and the animals, spirits, and people carved into the wood of the Pachacamac Idol once stood apart in vivid red, white, and yellow.

With the naked eye, no trace of color remains on the statue, but under a microscopic lense, small traces of red, white, and yellow pigment still hold on to the carved surface area, even after 1,300 years. The 2 upper figures’ headdresses were when vibrant red and yellow, while their faces were painted red and white. Littles red and yellow pigment still cling to a few of the animals and individuals in the middle sector.

” It may have even consisted of additional painted colors that have not been preserved,” wrote archaeologist Marcela Sepúlveda of the University of Tarapacá, Chile, and coworkers in a recent paper.

They used a non-destructive strategy called X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to take a look at those traces and learn what the pigments were made from. Each chemical element emits in a somewhat various wavelength of light when it’s bombarded with X-rays; by measuring those emissions, scientists can map the existence of different aspects on a things’s surface.

Enlarge / Spanish conquistadors mistook these traces of red pigment for dried blood, although some historians hypothesize that they may have made the claim in order to validate vandalizing the idol.

Sepulveda et al. 2020

A costly paint job

The XRF study exposed centuries of dirt in the carved recesses and crevices of the statue, along with a thick layer of varnish over the wood.

Based on artifacts at other sites around the Andes, along with descriptions in historic texts, we know that people in pre-Columbian Peru utilized cinnabar as a red pigment to decorate important objects and murals, as body paint for warriors in fight or nobility in important ceremonies, and as offerings to idols and effigies like the Pachacamac Idol. Cinnabar was the high-end alternative for painting things red; more common jobs made-do with easy iron oxide.

But for people at Pachacamac, the nearby source of cinnabar was about 350 km (220 miles) away at the Huancavelica mine in the central Andes. Transporting cinnabar cross countries for a specific function wasn’t unprecedented in pre-Columbian Peru, so the discovery wasn’t shocking. However, it does emphasize how important the idol must have been to the people who sculpted and painted it and set it up in the temple.

Enlarge / The base of the idol probably when suit a pedestal, the absence of which is most likely the fault of Francisco Pizarro.

Sepulveda et al. 2020

Who carved the idol?

The carvings match the style and motifs preferred by the Wari culture, which preceded the Inca in parts of Peru.

But then the Inca Tupac Yupanqui conquered the region around Pachacamac, including it to the Tawantisuyu Empire. As in their other territories, the Inca imposed sun praise as the primary religious beliefs, however they didn’t expect individuals to desert their own gods. Under the Inca, people at Pachacamac kept speaking with the Oracle as they had for centuries, even as the Inca built the website into a significant trip center to assist emphasize their own power. By the time the Spaniards showed up, the oracle resided in a dark vault in an upper chamber of the Painted Temple, one of two major temples in Pachacamac– and that’s precisely where archaeologists found it in 1938.

” The truth that it was taken care of with time regardless of possible modifications in the ceremonial practices at Pachacamac serves to emphasize the significance of the Idol,” wrote Sepúlveda and colleagues.

It wasn’t dried blood

By the time the Spaniards arrived, the sculpted statue might already have lost much of its color over the centuries, because the conquistadors describe the wood as filthy, not painted, other than for one reference of “dried blood” in its crevices. That ended up being cinnabar, likely from the same mine that later on supplied the mineral for the Spaniards’ silver processing.

Although the Spanish colonial rulers destroyed many Inca statues, ritualistic things, and murals in their efforts to wipe out indigenous religious beliefs, enough has made it through to offer us little glances into the colors of Inca religious life. Remains of murals in the Temple of the Sun and the Painted Temple at Pachacamac display people, marine life, and geometric patterns in black, green, red, white, and yellow.

However we don’t yet understand much about what those colors indicated to the people who worshipped there.

Today, the idol is a distinct and crucial piece of Peru’s indigenous heritage– precisely the example that’s difficult to based on destructive tests like radiocarbon dating. In this case, the statue had a natural hole in the blank lower section, and Sepúlveda and coworkers took a small sample from that for radiocarbon dating and tiny analysis. The XRF utilized to study the pigment is nondestructive but offers less information about the chemical composition of the pigments than other methods– however those other methods would require eliminating little samples of the pigment, which Sepúlveda and colleagues decided not to do “to preserve the traces that remain on this distinct object.”

PLOS ONE, 2020.